Every effort has been made to construct our clothing from fabric dyed in historically accurate colours. Fabrics are dyed with modern colourfast dyes which have been carefully matched to natural dye samples.

Although we offer deeply saturated colours, the majority of our hues fall into the medium tones and secondary colours which are more usual with natural dyes. In addition to primary blues, reds and greens, and we delight in the use of in between colours such as sage green, plum, gold, chestnut, salmon, rose, etc. Whenever possible, we avoid colours with the hard metallic intensity common with chemical dyes, opting instead for softer secondary colours.

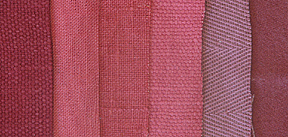

These images demonstrate the wide range of colours which can be achieved with natural dyestuffs...

Deep Colour Studio-

http://www.deepcolorstudio.com/images/gallerypics/singles.jpg

http://www.deepcolorstudio.com/images/gallerypics/yarn2.jpg

Kurt Laitenberger-

http://www.lindelwirt.homepage.t-online.de/pflanzf.jpg

True Colours Yarns-

http://www.truecoloursyarns.co.uk/turkish1.jpg

Use of Colors in Historical Clothing

In all cases the first bath yields the deepest, darkest and most expensive colours. Dyebaths were reused, and the second, third and fourth baths produced increasingly paler, less expensive shades. A very general rule of thumb to follow is that the deepest, richest and truest colors are the most costly to produce and should therefore be the purview of the upper classes. In general, the young and rich wear brighter colors than the old and poor. (Photo courtesy of Bryan Betts, www.temes.vikings.org.uk)

In all cases the first bath yields the deepest, darkest and most expensive colours. Dyebaths were reused, and the second, third and fourth baths produced increasingly paler, less expensive shades. A very general rule of thumb to follow is that the deepest, richest and truest colors are the most costly to produce and should therefore be the purview of the upper classes. In general, the young and rich wear brighter colors than the old and poor. (Photo courtesy of Bryan Betts, www.temes.vikings.org.uk)

For example, a young dandy might wear bright red, while his dignified father deep blood red or murray. A poor drover and a landed gentleman might each own a blue doublet or coat; that of the drover would be a thin grey blue, while the gentleman’s garment would be of luminous sapphire perse. A townswoman and a lady might both wear red gowns, but the townswoman’s gown would be a earthy orange red of madder, compared to the lady’s deep crimson gown of scarlet dyed in grain.

For more information on colour use and significance in the 14th and 15th C., please see the article "Textiles, dyeing and colour use"

The propriety of specific colours by class holds true for all periods- a Saxon gebur, Viking frjals or Norman villein would wear undyed wool in 'sheep' shades of creams, browns, and greys and unbleached linen. Their colour palette would include faded, inexpensive colours such as pale rusts and yellowy greens. A high ranking eorls, jarl or baron would wear fine, beautifully patterned wools dyed deep colours such as moss green, blue and red and have fine, bleached linens. (Photo courtesy of D. Y. Begay)

The propriety of specific colours by class holds true for all periods- a Saxon gebur, Viking frjals or Norman villein would wear undyed wool in 'sheep' shades of creams, browns, and greys and unbleached linen. Their colour palette would include faded, inexpensive colours such as pale rusts and yellowy greens. A high ranking eorls, jarl or baron would wear fine, beautifully patterned wools dyed deep colours such as moss green, blue and red and have fine, bleached linens. (Photo courtesy of D. Y. Begay)

For more specific information on Regia Anglorum's standards, please refer to their Basic Clothing Guide -Ranks and Colour Classifications page.

Availability

We know our customers don't want to look as though they've been stamped out of a mould. To ensure the unique nature of the garments we produce, we buy limited quantities of fabrics from dye lots and limit garment production quantities. Although we nearly always have a range of basic colours, there is little to no chance that the blue we were using 6 months ago will be the same blue we're using now, or that we'll be using next year. This makes it inconvenient for someone trying to match colours for a wedding, but it also means there's little chance of you attending an event wearing exactly the same colour as 4 other people at the event.

Because of our limited production policy, it would be impossible to keep a colour chart up to date. However, we know you'd like an idea of what our colours look like, so we've provided some swatches and colour information below.

Black

Many of our garments are not offered in black as dense, true black is an extremely difficult colour to achieve with natural dyes, especially when dying linen. Black required prodigious quantities of dyestuff and a fabric able to withstand the series of overdyes necessary to produce such a deep colour. For this reason true black was very costly to produce and out of the range of all but the most affluent during most of the medieval period. Visual sources and archaeological remains indicate that brighter, more colourful clothing were worn by the majority of people, and we offer a host of historical alternatives to suit every taste.

Black and other excessively dark and sombre clothing was extremely popular in the courts of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold in the late 15th C. and those who wished to associate themselves with those courts. Black and sombre colours were also affected by devoutly religious people as an outward display of piety.

As an accessory, black is a dramatic counterpoint to colourful clothing and black hats, shoes, boots, pouches, belts and other accessories are often seen in period artwork. You will find many of our accessories are available in black to set off your outfit.

Motley

Laura Hodges discusses 'motley' fabric in some depth in her book 'Chaucer and Costume'. "Mottelee has been variously defined...as 'polychrome' or multi-coloured....motlee was inexpensive to moderate in price....the best quality of motley might be fashionable..but it would not speak loudly of great wealth...it speaks discretely of economic moderation."

Based on what we know of the colouration of period sheep, fabric production, archaeological finds and written records, I believe a number of modern 'heather' and 'mottled' fabrics could easily fit the category of 'motley'. I like and use them because I think they represent a class of fabric which shows up frequently in the archaeological record but it underutilized in reenactment. For more information on the use of 'motley' fabrics in Black Swan Designs clothing, please refer to the following article...

The Use of 'mottled' or 'heather' fabrics in Black Swan Designs clothing.

Samples

Because we purchase limited quantities of materials, we have many shades of colour within a classification. These samples will give you an idea of the range of colours which fall under any given name. If you're looking for a very specific shade, please phone in and speak to someone- we're always glad to help! Likewise, we can recommend the most historical shades for the status, period and locale you're portraying.

Red

Colours in the red family are so easily obtained from so many sources that red and red derivative colours account for a disproportionately large part of colours represented in the historical record. The roots of the madder plant, cochineal, brazilwood and other dyestuffs yield a huge pallette of reds, rusts, oranges and pinks. Madder was native to Middle East but spread to northern Europe before 1066. It is a very fast dye which has been identified in many Medieval and Renaissance textiles.

Brazilwood (sappanwood) produces reds from the tree's heartwood. Native to Asia, this dye spread to northern Europe before 1200. Often used in combination with madder because of its tendency to fade.

Kermes, lac and cochineal are bugs whose bodies produce brilliant reds and purples. Kermes is native to Southern Europe, Lac to the far east, and various cochineals to Poland and parts of the Americas.

Scarlet, cardinal, murray, blood, red, brick, chestnut, russet

Brick, carnation, salmon, dusty pink, dusty rose

Orange

Madder with an alum/alkali mordant produces a rusty colour ranging from dark pumpkin to light apricot. Madder & cutch with a tin mordant produces a russet or chestnut red/brown.

Russet, chestnut, spice, apricot, caramel, copper

Yellow

Weld is the most common yellow dyestuff, producing a vivid, almost unbelievably electric yellow colour. Unfortunately, it is not a very fast colour and the intensity fades quickly. Buckthorn berries and Dyer's Greenweed also produce yellow dye. Both are native to Europe and are mentioned in medieval texts.

Yellow, gold, butter, maize, yellow-green

Green

Green is produced by overdying yellow with blue. Nettles with an iron mordant will produce a deep moss in the first bath and increasingly lurid yellow-greens in subsequent baths.

Dark Green, Moss, loden, spring green, sage, sea green, celery, pale green

Blue

Blues and greys come from the woad plant which is native to Northern Europe. Indigo is native to the Middle East and utilizes the same chemical as woad but in greater quantities. The dye from either plant (indigotin) can only be released via a complex fermentation process which relies on rather specific temperature, ph and oxidation requirements. Combining woad/indigo with yellow produces greens. Combined with red it produces lavender/purples.

Royal, dark royal, midnight, denim, navy, chambray, teal, marine, light blue

Purple

Purples and browns come from a number of native and imported dyestuffs. Alkanet, which is native to Southern Europe produces purple and grey. Logwood, lichens and murex produce purples, reds, and blue-violets. Orchil, or purple lichen, has been positively identified in medieval finds. Purples frequently overlap into brown tones.

Plum, dusty purple, lavender, burgundy, chestnut, blood red

Brown

Browns come naturally (as wool from brown sheep) as well as from a host of dyestuffs- walnut hulls, brazilwood, oak galls and/or oak bark, and lichen (Parmelia Saxatalis). Brown combined with purple yields a rich wine or plum colour; with red produces deep russets, chestnuts and burgundies, and with weld a range of golds and coppery hues. It has been observed the wool dyed with lichen dyes is not attacked by cloth moths, which accounts in part for the durability of lichen-dyed cloth.

Walnut, chocolate, tan, linen, pale apricot, spice, dark spice

Grey

Grey also comes naturally as wool from sheep or as a dyed colour. Grey wool can be the sheep’s colour, or it can be a result of black and white hairs spun together. An exhausted alkanet dye bath produces a pale lavender grey. Exhausted woad a pale slate blue-grey.

Charcoal, medium grey, silver, nickel

Lichens

Lichens account for a huge proportion of medieval domestic dyestuffs, probably more than we might realize. They are plentiful, relatively easy to collect, store and use. They produce a wide palette of colours, mostly in the brown-red-gold range.

"In certain districts of Scotland, as Aberdeenshire, almost every farm or cotter had its tank or barrel ("litpig") of putrid urine ("graith") wherein the mistress of the household macerated from lichens ("crotals" or "crottles") to prepare dyes for homespun stockings, nightcaps or other garments. The usual practice was to boil the lichen and woolen clothes together in water or in the urine-treated lichen mass until the desired color, usually brown, was obtained. This took several hours, or less on the addition of acetic acid, producing fast dyes without the benefit of a mordant or fixing agent. The color was intensified by adding salt or saltpeter. This method was prevalent in Iceland as well as in Scotland for those homespuns best known to the trade as Harris tweed."

Llano, G.A.. 1951. Economic uses of lichens. Ann. Rep. Smiths. Inst.: 385-422. Page 411.

Parmelia caperata- yellow

Parmelia conspersa- brown

Parmelia omphalodes- deep brown

(Parmelia centrifuga) yields red-brown dye for wool- Europe

(Lecanora calcarea): red-brown dye for wool- Sweden

Cetraria aculeata -brown dye for wool- Scotland and canary Islands

Cladina rangiferina- iron-red dye for wool - some parts of Europe

(Cladonia coccifera) yields red-purple dye for wool- Europe

Cladonia fimbriata- red dye for wool.

Cladonia gracilis- ash-green dye for wool.

Cladonia pyxidata: ash-green dye for wool.

Dermatocarpon miniatum- ash-green dye for wool

(Cetraria nivalis) yields violet dye for wool.

(Parmelia caperata) yields orange-brown to yellow dye - Isle of Man

(Parmelia physodes) yields brown dye for wool- Scandinavia, Scotland

Lobaria pulmonaria- orange-brown dye for wool- Scandinavia, Great Britain

Lobaria scrobiculata- brown dye for wool- Scotland and Scandinavia

(Parmelia acetabulum): orange-brown dye for wool- Northern Ireland

(Cetraria fahlunensis) yields red-brown dye for wool-Europe

(Parmelia olivacea) yields brown dye for wool- Great Britain

(Parmelia stygia) yields a brown dye for wool - Great Britain

Nephroma parile-blue dye for wool- Scotland

(Lecanora parella): violet dye for wool-France and Great Britain

(Lecanora tartarea): red or crimson dye..-Sweden and Scotland 1

Ochrolechia tartarea- reddish brown.- Scotland

Parmelia omphalodes- Yields purple-Red-brown dye for wool.

(crottle)Scandinavia, Ireland, Scotland

Parmelia saxatilis- orange, yellow, reddish brown dye (crottle)- Scotland,

western Ireland, Sweden

Peltigera canina- iron-red dye for wool- Europe

(Physcia pulverulenta) yields yellow dye for wool- Europe

(Cetraria glauca) yields a chamois-colored dye for wool- some parts of

Europe

(Sticta aurata)- Great Britain and Scandinavia

(Sticta crocata): brown dye for wool- some parts of Europe

Ramalina calicaris- yellow-red dye for wool- Europe

Ramalina cuspidata- light brown dye for wool- Europe

Ramalina farinacea- light brown dye for wool- Europe

Ramalina scopulorum- yellow-brown to red-brown dye for wool- Scotland

Rhizocarpon geographicum-brown dye for wool- Scandinavia

Roccella-Orchil, purple dye from Roccella spp. 2

Roccellaceae- Mideast-Rome

Stereocaulon paschale- ash-green dye for wool- some parts of Europe

(Cetraria juniperina): yellow dye for wool- Scandinavia

(Cetraria pinastri) yields green dye for wool-some parts of Europe

(Parmelia conspersa) yields red-brown dye for wool-England

Notes

1 Collected in May and June, steeped in stale urine for 3 weeks. Resulting

blackish mass is made into cakes and hung up to dry in peat smoke. Uphof,

J.C.T.. 1959. Dictionary of Economic Plants. Hafner, New York. Page 210.

2 Collected by the shipload from about 1450-1850- Richardson, D.H.S..

1991. Lichens and man. Pages 187-210 In Hawksworth, D.L., ed. Frontiers in

Mycology. Page 190.